Every day, a quarter of the world’s trade squeezes through the Malacca Strait.

But what if there was another way?

Thailand’s Kra Land Bridge promises a bold shortcut across the Isthmus that could reshape Asian trade.

What Is the Kra Land Bridge?

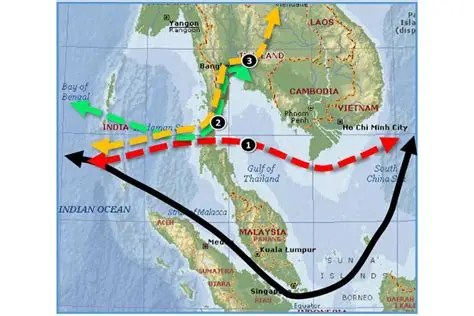

Thailand’s Kra Land Bridge (KLB) project is an ambitious and transformative infrastructure initiative that creates a direct cargo shortcut across Kra Isthmus, linking the Andaman Sea’s deep-water port at Ranong with a matching port at Chumphon on the Gulf of Thailand.

Spanning roughly 80 to 120 kilometers with highways, dual-track railways, and dedicated pipelines, this corridor aims to move cargo overland across the Kra Isthmus rather than ships, carving a significant shortcut for cargo that bypasses the congested Strait of Malacca.

The Canal That Never Was

The Kra Land Bridge is often compared with the long-discussed Kra Canal.

Proposals for the canal date back to 17th century when King Narai asked French engineers to survey the terrain. The idea resurfaced in the 19th century under colonial pressure. Later, a 1970s U.S. feasibility study found the Kra Canal too costly and disruptive. More recently, China promoted it under the Belt and Road Initiative, but fears of geopolitical leverage, separatist unrest, and ecological damage sidelined the canal idea paving the way for the Kra Land Bridge.

While a canal promised a direct maritime shortcut of up to 1,200 nautical miles, it faced barriers: construction costs exceeding $30 billion, severe environmental concerns, risks of dividing Thailand geographically, and fears of foreign dominance. For these reasons, successive Thai governments never advanced beyond studies.

How the Land Bridge Works

Unlike a sea canal allowing vessels to sail through, the KLB is a logistics corridor moving containers and other goods quickly between two ports where they are reloaded onto other vessels. This shifts one long sea voyage into two shorter sea legs plus a land leg. The cargo saves the time, not the ship.

Cargo vs. Ships: The Key Distinction

For example, a voyage from Colombo to Hong Kong usually covers about 2,900 nautical miles via Malacca. Through the land bridge, sea legs total approximately 2,250 nautical miles combined (Colombo → Ranong and Chumphon → Hong Kong), plus around 100 km (About 50 nautical miles) overland, saving cargo roughly 600 nautical miles. At around 13 knots, this can equate to a two-day shipping time advantage for the cargo. However, cargo must be transshipped between vessels at Ranong and again at Chumphon, requiring fast and efficient terminal operations including high-density gantry cranes, robust digital customs clearance, and reliable rail or truck transport to realize these time savings.

Navigational Impact: A Master Mariner’s View

As the master of large vessels frequently navigating one of the world’s busiest and most congested waterways ie. the Singapore Straits, I welcome the Kra Land Bridge. By diverting a significant volume of container and regional feeder traffic away from the Malacca and Singapore Straits, the KLB has the potential to reduce navigational risks. This decongestion can improve navigational safety and lessen bridge watch stress for seafarers.

Fellow seafarers similarly acknowledge that while they don’t gain a direct sailing shortcut, the corridor benefits cargo owners and smaller feeder vessels. It presents an operational and strategic win by easing choke points on critical shipping lanes, contributing to safer and more efficient maritime operations.

Kra Land Bridge Benefits for Shipowners

Shipowners stand to gain materially from the KLB project through up to 15% reductions in transportation costs and about four days saved on key Asia–India–East Asia routes by bypassing the Malacca-Singapore chokepoint. This translates into lower fuel consumption, reduced port fees, and improved operational efficiency by avoiding congested, high-traffic stretches in these narrow straits.

Even though a ship that might normally sail from Colombo to Hong Kong would instead stop at Ranong, with cargo transferred overland and reloaded at Chumphon, shipowners still benefit. Shorter voyages allow faster turnaround, better vessel utilization, and more efficient fleet deployment. The development of Ranong and Chumphon ports, along with feeder vessel networks, also creates new commercial opportunities, enabling shipowners to diversify freight routes and revenue streams in Southeast Asia.

Large-vessel operators who cannot practically use the land bridge model (such as VLCCs and bulk carriers) gain indirectly through reduced congestion and improved navigational safety in the Malacca and Singapore Straits, enhancing the reliability of their long-haul operations.

Advantages for Ship Managers

Ship managers gain operational flexibility with new port choices for calls and crew changes, storing, services etc. beyond traditional hubs like Singapore and Hong Kong, easing logistics complexities.

Cost savings from shorter cargo transit times and efficient transshipment lower fuel expenses and emissions, supporting environmental compliance goals. Additionally, alternative routing via the land bridge reduces piracy and operational risks, potentially lowering insurance premiums.

For managers balancing cost, risk, and fleet efficiency, the land bridge represents a chance to diversify operations and enhance resilience.

Why Not a Canal Instead?

The land bridge avoids these pitfalls. Instead of cutting through mountains and jungles, it uses ports, rail, and road to transfer cargo overland between Ranong (Andaman Sea) and Chumphon (Gulf of Thailand). This achieves many of the same trade benefits like reduced reliance on the congested Strait of Malacca without the geopolitical risks and environmental upheaval of a canal.

Geopolitical Stakes

This project extends far beyond logistics and commercial interests:

• Thailand’s Rising Regional Influence: Positioning Thailand as an indispensable logistics hub, challenging the dominance of Singapore and to an extent of Malaysia in maritime transshipment.

• Mitigating China’s “Malacca Dilemma”: China’s heavy reliance on the narrow Malacca Strait exposes vulnerabilities to blockades or geopolitical disruptions. The land bridge offers Beijing some relief from its ‘Malacca Dilemma,’ but unlike a canal, it does not hand China strategic control.

• Regional Competition and Realignment: This strategic recalibration comes with economic and political reverberations across ASEAN.

• Environmental and Social Concerns: Mangrove loss, fisheries disruption, and community displacement have sparked environmentalist warnings and call for balanced sustainable practices.

• Security Challenges: Southern Thailand’s history of unrest adds complexity to securing this vital infrastructure, demanding strong governance.

•Global Investment: The estimated 1 trillion Baht (~$28–36 billion USD) project attracts global investors, including Gulf states and multinational port operators.

Timeline and Outlook

The land bridge development will proceed in phases, with construction targeted to start in 2026 and the first phase operational by around 2030. Initial plans include sizable capacity ports (Ranong initially handling 6 million TEUs and Chumphon 4 million TEUs), a smart rail transit hub, and multi-lane highways, expanding in later phases to meet growing demand.

If executed with precision, combining fast cargo handling and secure railway operations, the Kra Land Bridge could shift regional trade patterns, promote sustainability, reduce maritime risks, and provide a genuine cargo transit shortcut with far-reaching economic and geopolitical impact.

Conclusion: Kra Land Bridge and the Future of Southeast Asian Trade

As a seasoned mariner, I see the Kra Land Bridge as a welcome operational advancement that promises reduced traffic congestion in some of the world’s most challenging straits, safer navigation for large vessels, and faster delivery for cargo owners.

Shipowners and ship managers stand to benefit from notable cost efficiencies, improved operational flexibility, new market opportunities, and reduced risks.

While the Kra Canal once promised dramatic sailing shortcuts, the Kra Land Bridge delivers its gains differently, by cutting inefficiency, not geography

Sources & Further Reading

· SeaTrade Maritime (2024): Thailand revives the Kra Canal but this time as a land bridge

· Delhi Policy Group (2023): Strategic Dimensions of Thailand’s Kra Land Bridge

· Nation Thailand (2025): OTP targets 2026 for bidding on 997.68 billion baht land bridge

· Channel News Asia (2023): Why Thailand’s proposed land bridge project is more feasible than the Kra Canal

· Eurasia Review (2025): Kra Canal — The Impossible Dream of Southeast Asia Shipping

· Napier University Research (2023): Opportunities and Challenges of the Kra Canal

Leave a comment