Amplitude remains one of the oldest techniques still taught and used in navigation. It survives because it is simple, quick, and independent of electronics. A rising or setting Sun gives the navigator a direct check on compass error using nothing more than a bearing and a table. Even on modern bridges fitted with integrated electronic navigation systems, this simplicity remains its strength.

Yet amplitude is also a misunderstood topic in basic navigation. This is not because the method is difficult, but because theoretical definitions, visual descriptions, and examination shortcuts are often mixed together without explanation. Over time, this has led to rules being memorised without a clear understanding of what they represent.

This article does not propose a new way of taking amplitude, nor does it challenge established books or examination practice. Its purpose is only to explain how the method fits together and why the familiar descriptions exist.

It is not intended to teach the calculation of amplitude, but to clarify a few fundamental points that affect how it is applied in practice, particularly the reference horizon, timing of observation, the use of visual limb descriptions, and the role of correction tables at higher latitudes.

In principle, amplitude can be determined for any celestial body that rises or sets. In practice, the Sun is the most commonly used body because it is clearly visible against the horizon and has a well-defined apparent disk, making the observation straightforward and reliable.

What amplitude actually represents

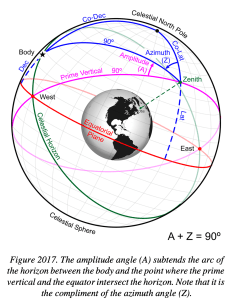

Amplitude is the angular distance of a celestial body east or west of the true east–west point of the horizon at the time of rising and setting. In navigation, it is obtained by comparing the observed bearing of the Sun near the horizon with a value taken from tables or calculated from the body’s declination and the observer’s latitude.

For the navigator, amplitude is therefore a bearing relationship associated with rising or setting. A bearing of the Sun is observed close to the horizon and compared with the corresponding amplitude to determine compass error. Used in this way, the method is simple and requires very little computation.

When amplitudes are tabulated or calculated, however, an exact astronomical reference must be defined. This reference does not correspond to any visible line on the sea and cannot be identified directly by the observer. The difference between this theoretical horizon and the visible horizon is the source of much of the confusion surrounding amplitude.

Understanding amplitude therefore depends on keeping these two ideas separate ie. the theoretical condition assumed by the tables, and the practical observation made on the bridge.

The horizon used by the tables and the horizon we see

In practice, amplitudes are obtained from Norie’s Nautical Tables, using the Sun’s declination taken from the UKHO Nautical Almanac. The theoretical basis for these tables is explained in standard texts such as Bowditch.

The amplitudes given in these tables are referenced to a defined astronomical condition associated with rising or setting, in which the centre of the celestial body is lying on the celestial (rational) horizon. This horizon is a geometric plane passing through the centre of the Earth and perpendicular to the direction of gravity. It is a mathematical reference, not a line that can be seen.

On the bridge, the navigator works with the visible horizon. Because the observer is above sea level and because atmospheric refraction bends light near the horizon, the visible horizon lies below the celestial horizon. As a result, the condition assumed by the tables cannot be observed directly.

Because the visible horizon lies below the celestial horizon, the Sun does not appear with its centre on the horizon at the moment assumed by the tables. Instead, part of the Sun is already visible above the sea horizon.

It is simply a consequence of observing from above the Earth’s surface through an atmosphere. A visual cue is therefore needed to recognise the theoretical moment used by the tables.

The navigator therefore requires a practical way to recognise, by eye, the theoretical moment on which the tables are based. This is the sole reason visual descriptions enter the method.

Why the Sun’s disk enters the discussion

The Sun’s radius is about 16 minutes of arc. Amplitude is defined with reference to the centre of the Sun, but the centre cannot be seen against the horizon. Because the celestial horizon itself is not visible, navigator needs a way to relate a theoretical condition to something visible.

That need gave rise to descriptive statements such as:

“The Sun appears about half to two-thirds of a diameter above the horizon.”

This description answers only one question, what the Sun looks like when its centre is on the celestial horizon. It is simply a visual indicator of a theoretical position already defined by the tables.

The wording is intentionally approximate. The apparent height of the disk varies slightly with height of eye, atmospheric conditions, and latitude, which is why navigation texts use terms such as about or approximately.

The origin of this visual rule is purely geometric. Near the horizon, mean atmospheric refraction is approximately 34′, and dip for a typical bridge height adds several more minutes of arc. Together, these effects raise the apparent position of the Sun’s centre to about 40′ relative to the celestial horizon. Since the Sun’s apparent diameter is about 32′, the moment when its centre is on the celestial horizon corresponds visually to the disk appearing more than half a diameter above the visible horizon. This is why navigation texts describe the condition approximately, rather than as a fixed fraction.

When the Sun’s centre is on the celestial horizon, refraction and height of eye cause part of the disk to appear above the visible sea horizon. This appearance is used only as a visual indicator of the theoretical condition assumed by the tables.

Rising, setting, and the question of limbs

Confusion often arises because descriptions of the Sun’s disk are sometimes mixed with everyday language about sunrise and sunset, where people naturally think in terms of which limb of the Sun appears or disappears first.

For amplitude, however, the reference is always the position of the Sun’s centre relative to the celestial horizon. When that condition is met, the Sun’s disk appears displaced above the visible horizon by the same amount whether the Sun is rising or setting. Atmospheric refraction and dip act in the same way in both cases.

For this reason, references to the Sun’s limbs in navigation texts are descriptive aids only. They exist to help the observer recognise, by eye, the theoretical moment associated with rising or setting. They do not introduce different rules for sunrise and sunset, and they do not change the reference used for amplitude.

What examination and bridge practice actually do

In examination work and routine navigation, amplitude is usually obtained without applying any explicit correction.

The usual procedure is to take the Sun’s declination from the Nautical Almanac, obtain the corresponding amplitude from Norie’s tables or by calculation, observe the Sun near the horizon using the accepted visual indication, and compare the observed bearing with the tabulated value.

Latitude appears in the calculation because amplitude depends on latitude. This is part of the geometry of the problem, not a correction applied by the observer.

No separate numerical correction is normally applied for observing on the visible horizon. The method assumes a standard apparent observation that corresponds closely enough to the theoretical condition for practical purposes.

What Amplitude correction tables tell us

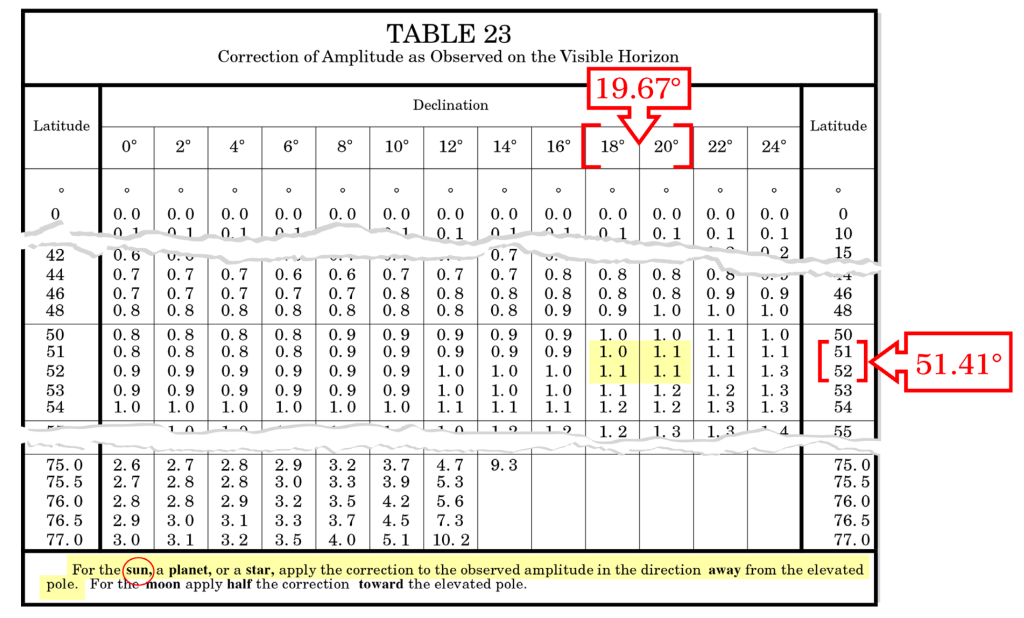

Amplitude correction tables quantify the difference between amplitudes referenced to the visible horizon and those referenced to the celestial (rational) horizon.

The magnitude of this difference depends on both latitude and declination. At latitude 0°, the correction is zero. As latitude increases, the difference becomes larger, particularly for higher declinations. At higher latitudes, the Sun’s apparent motion near the horizon is shallower, which makes the difference between the visible horizon and the celestial horizon more noticeable.

This explains why the traditional visual method works extremely well at low and mid-latitudes, and why greater care may be required at higher latitudes if increased accuracy is desired.

These correction tables do not alter the definition of amplitude, nor do they imply that routine practice is incorrect. They simply make the reference explicit and provide a means of refinement when higher accuracy is required.

Declination and the Nautical Almanac

Declination taken from the Nautical Almanac is a geocentric astronomical quantity, referring to the position of the Sun’s centre relative to the celestial equator. It is independent of the observer’s latitude, the horizon used, refraction, dip, or the method of observation.

No amplitude-related correction is applied when declination is taken from the Almanac; any horizon-related effects arise later through geometry or explicit correction tables.

Operational considerations in practice

In practice, amplitude may be obtained by table, calculator, or manual calculation, but the sources of error are the same regardless of method. All approaches rely on correct inputs of date, time, latitude, and declination, and on the observation being made at the appropriate stage of rising or setting. An error in any of these will produce an incorrect result, irrespective of the tool used.

Portable navigation computing devices, including Tamaya-type calculators, perform calculations based on internal astronomical models and user-provided data. They do not determine declination by observation, nor do they remove the need for sound judgement. Similarly, general-purpose mobile applications and unofficial software tools or unofficial xls sheets may not clearly state the assumptions on which their results are based, making independent verification essential.

Amplitude is particularly sensitive to timing. Near rising and setting, the Sun’s azimuth changes rapidly, and a bearing taken too early or too late can introduce a noticeable error even if the subsequent calculation is correct.

Correction tables further show that the difference between amplitudes referenced to the visible horizon and those referenced to the celestial horizon increases with latitude. At low and mid-latitudes this difference is usually small and of little consequence for routine compass error checks, but it becomes more significant at higher latitudes if greater accuracy is required.

For simple amplitude determinations, no specialised software is necessary. When timing is correct and latitude and declination are taken accurately from authorised references, basic tables or straightforward calculation are sufficient; additional tools do not improve accuracy, they only reproduce the same geometric result.

Final perspective

Amplitude is more than a memorised visual cue; it is a simple piece of spherical geometry applied at the horizon. Amplitude has not changed, and neither have the books. What often goes missing is a clear explanation connecting theory, tables, and what the observer actually sees.

Once that connection is restored, amplitude becomes what it has always been, a simple piece of geometry, applied with practical judgment, and still useful on a modern bridge.

References

- Norie’s Nautical Tables

- Bowditch – The American Practical Navigator

- Navigation for Masters – D. H. House

- UKHO Nautical Almanac

Leave a comment