What They Are, How They Work, and Why Owners Are Installing Them

Part 1 of 2

Tall rotating cylinders are now appearing on the decks of commercial ships. They stand out because they do not resemble anything traditionally associated with propulsion. Installed on bulk carriers, tankers, ferries and other cargo vessels, they are now being presented as functional propulsion devices rather than experimental add-ons.

These structures are Flettner rotors, now commonly referred to as rotor sails. The underlying principle was first demonstrated at sea in 1922, when Anton Flettner fitted rotating cylinders to a merchant vessel and showed that aerodynamic lift could be used for propulsion. The physics has not changed since. What has changed is the environment in which the technology has returned.

Their reappearance in commercial shipping is not driven by novelty. It is driven by operating and regulatory pressure. Before asking whether these systems deliver what is claimed, it is necessary to first establish what they are intended to do, the physics they rely on, and why shipowners consider them commercially viable today. This article sets that foundation. Performance comes later.

The first commercial demonstration of rotor-assisted propulsion, developed by Anton Flettner.

What a Flettner Rotor Is

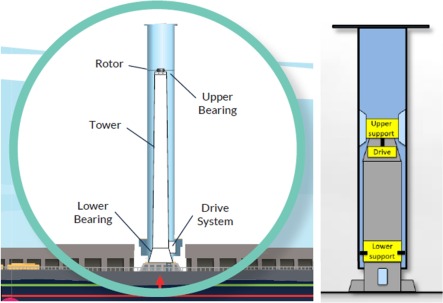

A Flettner rotor is a vertical cylindrical structure mounted on a ship’s deck and rotated around its vertical axis by an electric motor. As air flows across the rotating surface, an aerodynamic force is generated. When wind direction and vessel heading align, part of that force acts in the direction of travel.

The rotor works alongside the main engine. It reduces the propulsive load required to maintain speed. The propeller remains the primary source of thrust. The rotor assists when conditions allow.

Although commonly called a rotor sail, it behaves differently from anything traditionally used at sea. It does not depend on surface area resisting the wind. It does not require trimming or adjustment by the crew. Its output is controlled through rotation speed rather than geometry.

What it produces is lift. Controlled, predictable lift.

A vertically mounted, motor-driven cylinder.

The Physics, Without Ornament

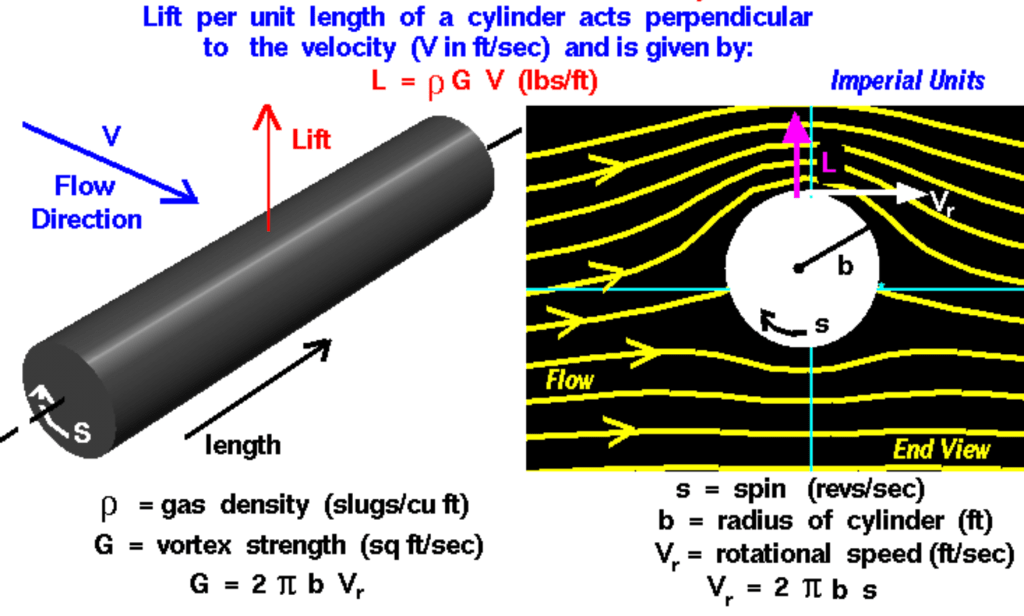

The operating principle of a Flettner rotor is the Magnus effect. It describes the force generated when a rotating body interacts with a moving fluid, in this case air.

As air flows past a rotating cylinder, the surface motion increases airflow velocity on one side and reduces it on the other. Higher velocity produces lower pressure. Lower velocity produces higher pressure. The resulting pressure difference generates an aerodynamic force perpendicular to the direction of airflow.

That force is lift.

On a ship, the relevant flow is the apparent wind, not the true wind. Apparent wind is the vector sum of true wind and vessel speed. The rotor responds only to what it experiences at deck level.

When the apparent wind approaches from the side or at an oblique angle, the lift vector can be resolved into components. One component acts sideways. Another acts forward. It is the forward component that reduces the propulsive effort required from the propeller.

The effect is strongest in beam winds. It weakens as the wind shifts toward the bow. In headwinds, the forward component becomes negligible. In calm conditions, no useful force is generated regardless of rotation speed.

The magnitude of the force depends on rotor height and diameter, surface speed, apparent wind angle, wind velocity, and vessel speed. These relationships are well understood and predictable.

Rotation creates a pressure difference, generating lift perpendicular to the airflow.

Why It Returned

Flettner rotors have reappeared in commercial shipping after decades of absence. Their return coincides with a shift in how ship performance is evaluated.

Fuel consumption has always mattered. Today it is visible. Efficiency and emissions are tracked, scored, and compared across fleets and trades. Performance is assessed beyond the ship and beyond the owner.

Rotor sails reduce fuel consumption when wind conditions allow. Reported reductions typically fall in the range of five to fifteen percent, depending on route, season, and vessel speed. The mechanism is consistent. The outcome varies.

The electrical power required to rotate the cylinders is small relative to the propulsive power they offset. When apparent wind conditions are favourable, the net balance remains positive.

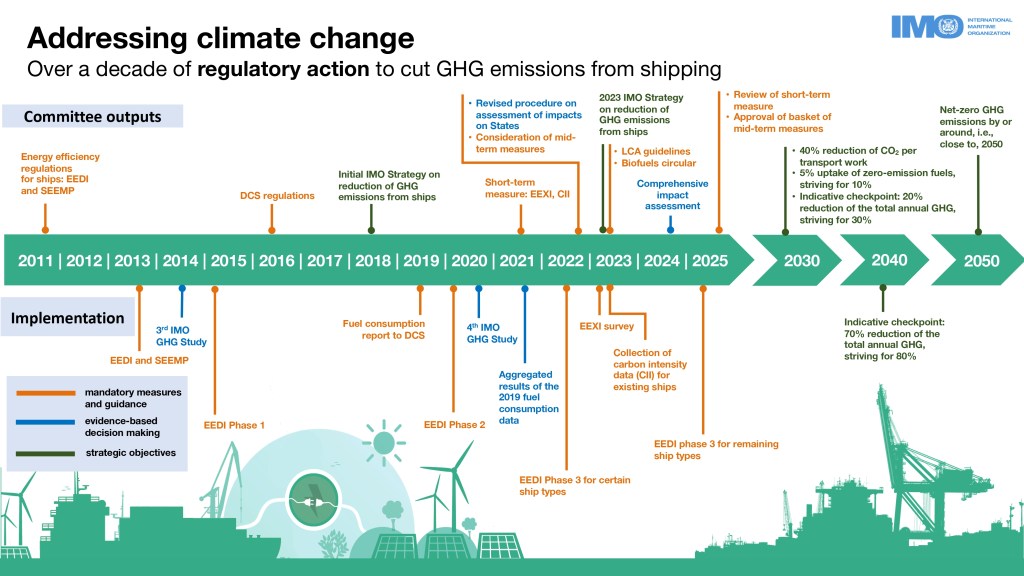

Their contribution extends beyond fuel savings. Reduced consumption is reflected directly in measured efficiency and carbon-intensity metrics used under current regulatory frameworks.

Their reappearance aligns with how shipping performance is now measured. What has changed is the way performance is observed.

Decarbonisation Pressure and the Shipping Narrative

Shipping has become a focal point in the climate discussion by virtue of visibility rather than proportion. Global trade depends on shipping, yet emissions accounting increasingly isolates the ship from the cargo it carries, the supply chains it serves, and the demand that determines the voyage.

In this framing, the ship is convenient. It is mobile but trackable, international but regulatable, and technically complex but administratively reducible to metrics. That makes it easy to measure and easier to assign responsibility.

Regulatory mechanisms such as the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI) and the Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) have reinforced this approach. Attention has shifted from absolute emissions across supply chains to intensity-based scores applied at the vessel level. Operational decisions are now shaped as much by how performance is recorded as by how it is achieved.

These metrics increasingly feed into broader ESG reporting frameworks used by charterers, lenders, and cargo interests.

Within this environment, a rotor sail offers more than fuel reduction. It alters reported outcomes. Lower fuel burn improves CII ratings. Supplemental aerodynamic thrust is reflected in efficiency indices used under current compliance regimes. For vessels operating near regulatory thresholds, this margin often carries greater significance than the fuel saving itself.

Rotor sails also carry signalling value. They are visible installations with an easily communicated purpose. In charter markets increasingly influenced by emissions reporting and environmental positioning, visibility has commercial weight.

Decarbonisation in shipping is therefore shaped by measurement frameworks as much as by physical energy flows.

The Commercial Calculation

From an owner’s perspective, the calculation is straightforward.

A rotor installation typically costs several hundred thousand to over a million dollars per unit, depending on size and configuration. Additional costs sit around it: structural reinforcement, electrical integration, automation, and class approval. Ongoing operating costs remain limited, largely confined to power consumption and routine maintenance.

The return comes from incremental fuel savings when wind conditions allow, combined with improvements in measured efficiency and regulatory margin. Reported payback periods commonly fall in the range of three to seven years, depending on fuel price assumptions, vessel profile, and route exposure.

Some installations will fall short of these projections. Others will exceed them. All are evaluated on models before steel is cut.

The variability is inherent to the model.

Structural and Operational Boundaries

In service, Flettner rotors operate within a defined envelope.

They perform best on long passages with persistent cross-winds. Their contribution reduces as wind shifts forward and disappears in calm conditions. Installation consumes deck space, adds weight high above deck, and introduces concentrated loads that must be carried into the hull structure.

Clearance under bridges, interaction with cranes and cargo operations, radar shadowing, and airflow disturbance around accommodation and funnels must be resolved at the design stage. These are known constraints, not operational surprises.

Stability effects are manageable but material. Vertical centre of gravity, wind heeling moments, and dynamic loading require formal assessment and class approval.

These factors define the conditions under which the system delivers value.

Why This Foundation Matters

Flettner rotors are aerodynamic devices operating within a variable physical and regulatory environment. Their performance depends on conditions as much as design.

Understanding what they are intended to do, and the context in which they are being installed, is necessary before judging outcomes.

Part 1 sets out the hardware, the physics, and the commercial and regulatory setting.

Part 2 will examine execution: variability in performance, measurement in practice, and what emerges when modelling assumptions encounter weather, schedules, ports, and human decision-making.

Sources and Technical Material

- International Maritime Organization, GreenVoyage2050 Technology Portal, wind-assisted propulsion systems

- IMO MEPC documentation on Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI) and Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII)

- DNV, Wind-Assisted Propulsion Systems – technology outlook and case studies

- Lloyd’s Register, guidance notes on rotor sail structural integration and operational considerations

- University of Strathclyde engineering material on the Magnus effect and rotating cylinder aerodynamics

- Anton Flettner, historical documentation on rotor ships and early trials

Leave a comment