The Question That Always Comes Next

In my previous article, I explained how sanctions enforcement, particularly through OFAC, reaches the ship and why the Master becomes involved.

https://thedeepdraft.com/2025/12/15/ofac-sanctions-ship-master/

What almost always follows is a different assumption, especially from readers ashore –

“Surely the crew knows where the vessel is trading.”

“Surely the Master knows what kind of trade this is.”

“Surely they know this is a Russia, Venezuela, or Iran route.”

These statements assume that sanctions work like geographical restrictions, where sailing to certain countries automatically makes a ship sanctioned. That assumption is incorrect.

Sanctions are not global maritime bans. They are jurisdiction-specific legal restrictions imposed by individual states or blocs. A voyage to Russia, Venezuela, or Iran may be illegal for the United States, restricted for EU or UK operators under services bans or price-cap regimes, and still lawful for Chinese or Indian buyers using non-coalition finance, insurance, and services.

This is why such trades are often described as grey rather than uniformly illegal. The risk does not arise from the route itself, but from which banks, insurers, currencies, service providers, and counterparties touch the transaction. The Master may know the route, but he does not control and often cannot see which sanctions regime the supporting chain ultimately falls under.

How Seafarers Actually Join Ships

Most seafarers do not join ships independently. They join through recruitment and placement agencies operating within national regulatory frameworks.

By country, this typically looks like:

- India

Recruitment agencies operate under a Recruitment and Placement of Seafarers Licence (RPSL) issued by the Directorate General of Shipping. - United Kingdom

Recruitment and placement of seafarers is subject to oversight under the Maritime Labour Convention framework, with the Maritime and Coastguard Agency acting as the competent authority. - United States

Mariner recruitment operates within a federal regulatory framework. The United States Coast Guard is responsible for mariner certification and manning standards, while recruitment and employment are governed by U.S. labour and contract law. - China

Crewing agencies operate under a state-regulated system, with licensing and supervision involving the China Maritime Safety Administration and associated labour authorities. - Philippines

One of the world’s largest seafarer supply hubs, where crewing agencies are licensed and regulated by the Department of Migrant Workers, which absorbed the former functions of the Philippine Overseas Employment Administration.

In practice, this means that the recruitment agency is responsible for ensuring that, at the time of joining, the crew is placed on a vessel that is lawfully engaged and properly documented under the regulatory standards the agency is authorised to oversee.

Under the Maritime Labour Convention, 2006 (MLC), recruitment and placement services must be licensed or certified, audited by the administering authority, and meet standards on legality and seafarer protection.

What the MLC does not regulate is sanctions exposure. It deals with lawful recruitment and crew protection at the time of joining, not with sanctions enforcement linked to cargo ownership, financing, insurance, or services that may develop later.

Expecting a crew member to identify or predict sanctions exposure goes beyond what the crewing framework is designed to provide.

Knowing the Route Is Not Knowing the Sanctions Risk

A common assumption ashore is that sanctions risk should be obvious to anyone onboard simply by knowing the vessel’s route.

That assumption is incorrect.

A route is a navigational fact.

Sanctions risk is a legal and financial assessment.

A Master may know that a vessel is trading to or from politically sensitive regions. That knowledge alone does not determine whether the voyage is lawful, restricted, or sanction-exposed. There is no such thing as a universally “sanctioned route” under international maritime law.

Sanctions attach to transactions, not on the route, port calls or geography. They depend on who owns the cargo, who pays for it, which banks clear the payments, which currency is used, which insurers and reinsurers are involved, and which service providers fall under particular jurisdictions.

From the bridge, what is visible is limited to ports, cargo declarations, and sailing instructions. What matters most for sanctions is that the financial and services chain exists entirely ashore.

Sanctions risk is therefore often identified after the voyage, once transactions are reviewed and patterns across multiple voyages are assessed. Expecting Masters or crews to infer that risk in advance confuses hindsight with foresight.

Why “You Must Have Known” Is a Weak Assumption

Knowing where a ship is going does not mean knowing –

- who paid for the cargo

- which banks handled the money

- whether reinsurance was involved

- whether secondary sanctions apply

- when a pattern across voyages becomes visible

These factors only emerge when data is aggregated and reviewed over time.

Sanctions enforcement works backward.

Shipboard operations move forward.

This gap is where most misunderstandings arise.

Why Maritime Law Does Not Control Sanctions Enforcement.

Maritime law governs navigation, flag-state control, and conduct at sea. Sanctions enforcement operates on a different plane. It works through financial and services jurisdiction, not through a general right to stop or board ships on the high seas.

Recent incidents involving vessels such as Talara, Clipper, MT Centuries, and other tankers operating near Iran, Venezuela, Russia-linked trades, or high-risk corridors are often cited as examples of “sanctions enforcement at sea.” These cases are familiar to maritime professionals and frequently invoked in public debate. Their prominence has been amplified by a growing number of tanker attacks and drone strikes linked to the Russia–Ukraine conflict, including commercial vessels targeted well beyond declared war zones.

This has reinforced a persistent misunderstanding. Sanctions law does not authorise physical enforcement at sea. Whatever legal bases were asserted for such boardings or attacks, whether claims of flag-state consent, statelessness, bilateral arrangements, or security authorities lie outside sanctions regimes. They are separate from the financial and services controls through which sanctions are actually enforced.

This distinction matters. Sanctions pressure is usually felt ashore, through withdrawal of insurance, refusal of port services, frozen payments, or loss of commercial support not through routine intervention at sea.

A vessel can therefore be fully compliant with maritime law and still face sanctions pressure because of how the trade is financed and supported ashore. Maritime law governs movement. Sanctions law governs transactions. Confusing the two leads to false assumptions about enforcement powers and misplaced expectations of Masters and crews.

A Practical Reality Check Masters Can Do

Sanctions scrutiny is now part of normal shipping risk. There are basic checks a Master or senior officer can carry out to understand the risk environment.

These checks do not replace shore-side compliance. They help the Master stay informed.

1. Sanctions List Checks

- OFAC Sanctions Search (USA)

https://sanctionssearch.ofac.treas.gov/ - UK Sanctions List (OFSI)

https://search-uk-sanctions-list.service.gov.uk/ - EU Sanctions Map

https://www.sanctionsmap.eu/ - UN Security Council Consolidated List

https://www.un.org/securitycouncil/content/un-sc-consolidated-list

Absence from a list does not mean the trade is risk-free.

2. Vessel History and Stability

- EQUASIS — https://www.equasis.org

- VesselFinder — https://www.vesselfinder.com

- MarineTraffic — https://www.marinetraffic.com

They reveal patterns but do not prove compliance.

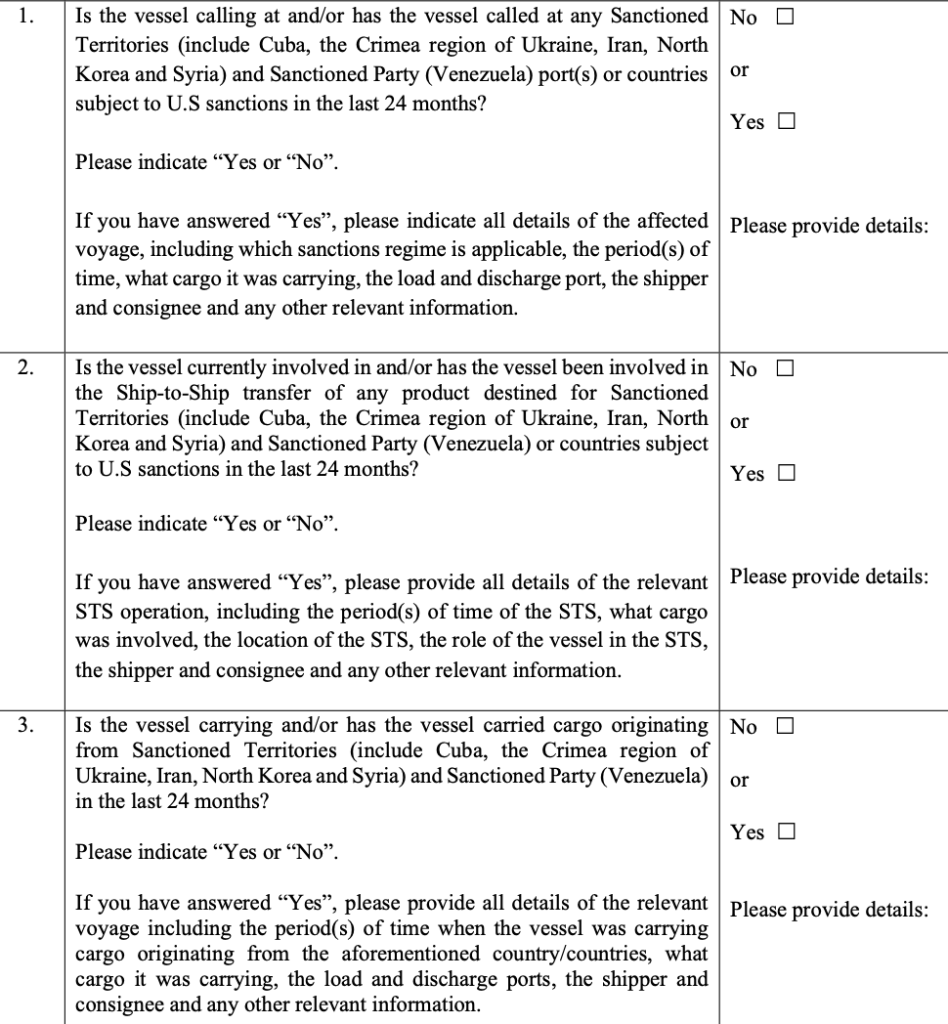

3. STS Awareness

Ship-to-ship transfers are lawful, but repeated STS activity in certain regions attracts scrutiny. Awareness is essential.

What Is Unrealistic to Expect

It is unrealistic to expect a Master or crew to:

- trace cargo financing

- follow banking or payment routes

- assess secondary sanctions exposure

- predict enforcement triggered by patterns across voyages

Those responsibilities sit ashore with those who structure the transaction and control money, insurance, and services.

This article explains why knowing a route is not the same as knowing the sanctions exposure of a trade. Sanctions risk is assessed ashore, often after the voyage, while responsibility for factual documentation sits onboard.

Understanding this gap is essential if sanctions discussions are to remain grounded in operational reality rather than assumption.

Disclaimer

This article is written from an operational and professional perspective. It does not provide legal advice, make findings of legality or illegality, or assess compliance under any specific sanctions regime.

Leave a comment