Professionalism of Japanese Pilots and Shore-Side Teams – A Comparison with Other Ports

There are ports where pilotage feels like an act of experience, and there are ports where it feels like an act of engineering.

In Japan, it is both experience embedded inside engineering.

Over the years I’ve handled ships through every major pilotage environment, the Mississippi River in North America, the Magdalena River in Colombia, the Amazon, the Suez and Panama canals, the approaches of North China, Singapore’s congested anchorages. I have worked with American pilots steering by current overlays, Amazon pilots navigating confidently where the chart shows land, Indian ex-masters who carry command judgement into pilotage, and Singaporean pilots who operate a VLCC’s main engine with joystick-like precision.

I say this because I have seen the opposite in many places, good pilots operating inside weak systems. Japan is the other end of that spectrum.

Across regions, pilotage styles change, but one lesson remains constant: a pilot’s skill is at its best only when supported by a disciplined, well-designed system.

Planning: Precision Begins a Week Before Arrival

In Japan, a ship’s pilotage time is fixed at least a week in advance. The first message from the agent or pilot office is much more than boarding times. It includes –

- Which side the vessel will berth.

- How mooring lines will lead and from which winch.

- The exact location where each tug will be made fast.

- Tug horsepower, call signs, and weather forecasts.

By the time the pilot steps on board, the entire manoeuvre exists on paper. Every ship receives a region-specific pilot booklet in a uniform national format containing tide and current tables from JCG hydrographic data, traffic routes, signal explanations, AIS-setting instructions, and sunrise and sunset times.

The Pilot Cards – Engineering the Approach

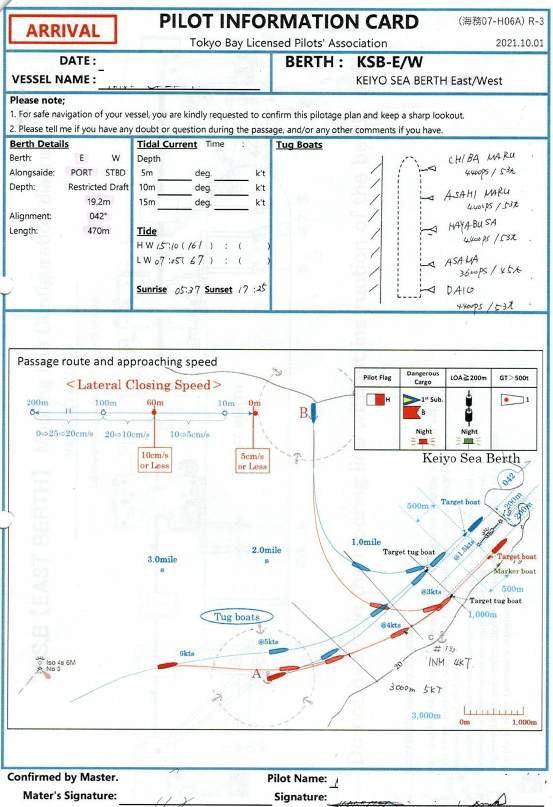

During approach, the pilot carries the Pilot Information Card which is not a generic form, but a hand-annotated version studied and prepared for that specific voyage. Pilot cards exist in many ports today, but the precision and discipline with which they are used in Japan are on a different level.

Each card includes:

- A passage track from boarding point to berth, drawn to scale.

- Speed targets stepping down: 10 → 8 → 6 → 4 knots.

- Lateral closing speeds plotted in metres per second.

- The timing and position for tug engagement.

- Speed limits for each route segment.

- The pilot’s alcohol-test reading, reflecting a culture of personal accountability.

- Boxes for “Passage Plan Confirmed by Master” and “Confirmed by Pilot.”

I remember a pilot who quietly placed the card on my chart table before we spoke. His handwriting was immaculate. He pointed to a simple line,“keep about 200 m away from the berth north end”, smiled, and said, “We will follow exactly this.”

In that moment, professionalism felt less like hierarchy and more like precision shared between two mariners.

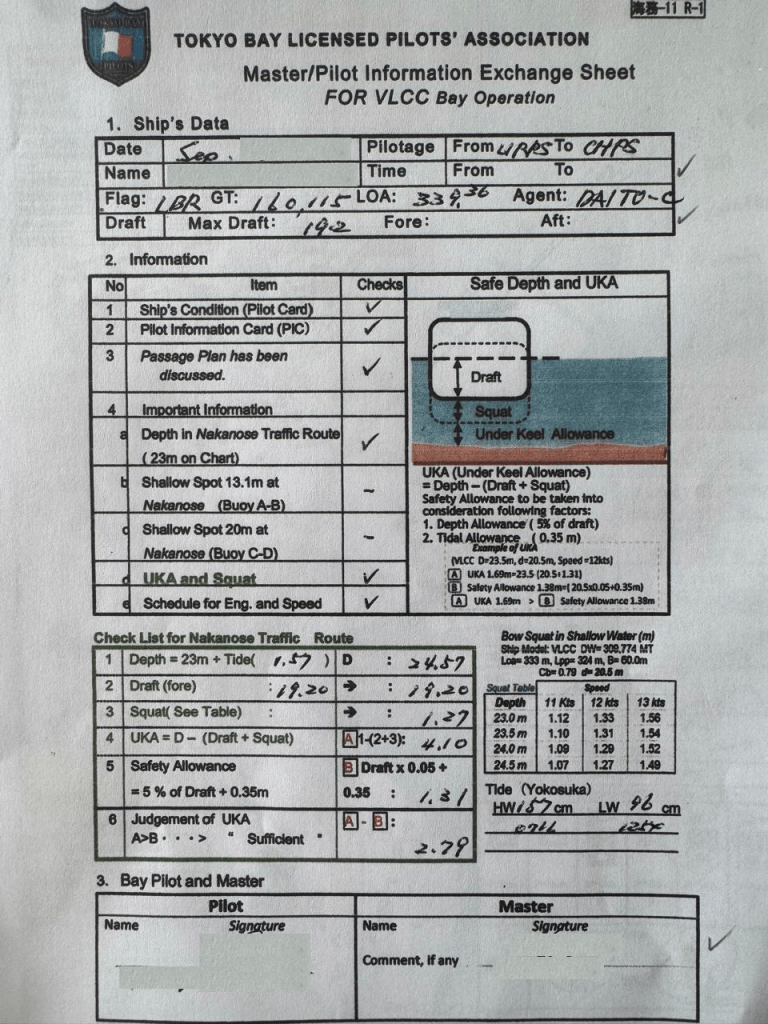

The Exchange Sheet(MPX)

Before arrival or departure, the Master–Pilot Information Exchange Sheet is completed. It lists under-keel clearance (UKC), squat allowance, safe depth, and expected tide rise, all verified and signed by both Master and Pilot. Nothing is left ambiguous.

In most ports, pilots rely on familiarity rather than formal UKC or squat calculations. In Japan, the pilot arrives with his own verified sheet based on real-time tidal data. In my case, he even asked to compare his UKC figures with mine, a level of cross-checking almost unheard of elsewhere. In many places, the ship’s UKC figures and the pilot’s local assumptions rarely align perfectly.

Japan treats this exchange not as paperwork but as discipline. Each figure UKC, tide height, draft, squat is reviewed against hydrographic and terminal data before signing.

That sheet represents more than procedure, it represents shared accountability:

“We have seen the data; we are proceeding together.”

Berth Masters and the Shore-Side Discipline

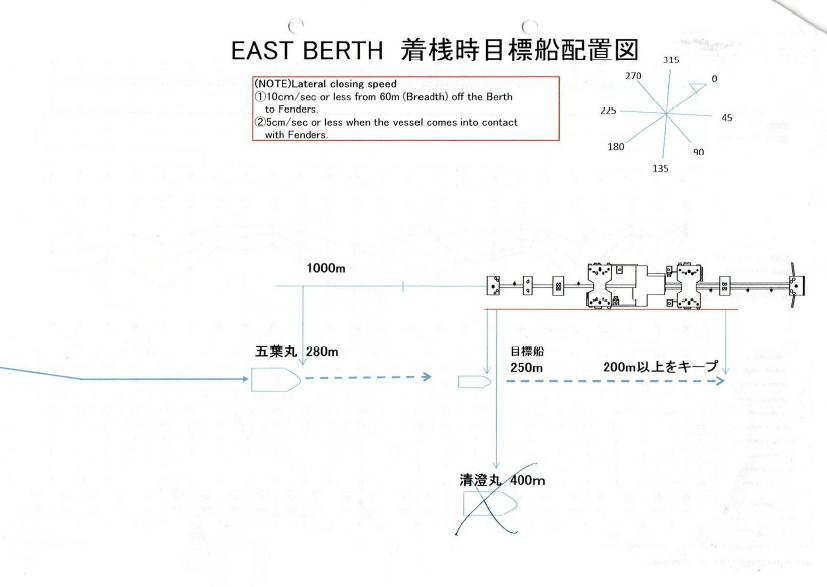

As the vessel closes in on the berth, another layer of professionalism appears, the Berth Master and his team. Before the operation, the Master, Pilot, and the shore-side team review a standardized Berthing Operation Information Card used in that port district detailing real-time currents at multiple depths, speed thresholds for each ship class, and clear stop criteria when wind and current oppose each other. The plan is exact, maintain one knot as the bow passes the berth end, hold a 200-metre clearance, confirm three current checks.

Once alongside, the same discipline continues. Mooring and unmooring sequence diagrams are distributed in advance, showing exactly which line to handle first, which to hold, and which remains until “last line clear.” The instructions are simple:

“Do not heave in the mooring line without instruction of the berth staff.”

There is no shouting, no disorder. Communication on the berth is stripped down to its essentials. The mooring crew and Berth Master do not wave hands, shout, or use improvised phrases. Everything works on whistle codes. One whistle stops the crew. Another whistle starts the operation. Nothing more. No local slang, no finger language, no confusion. It is a clean, binary system where a single sound carries a single meaning, and every person on the jetty and every person on the bridge understands exactly what is about to happen. Tug masters, pilots, and berth staff communicate in short, standard phrases. Courtesy here is not cultural decoration, it is an operational safety tool. Predictability begins with respect.

Manoeuvring Philosophy: Not Skill but System

In many parts of the world, a ship manoeuvres almost up to the fenders before spring lines bite. Engines remain the main tool till the last seconds. Japan follows a different philosophy. A VLCC is held about two hundred metres in line with the jetty, and the rest is pure tug work. Five tugs are made fast, three pushing and two pulling, and the entire movement becomes controlled, predictable, and almost engine-independent. Many foreign mariners laugh at the idea of using so many tugs, but the outcome is simple, the manoeuvre stays safe, steady, and free of last-moment surprises. This is not about higher skill but about a system designed to keep forces low, margins wide, and the ship under absolute control.

Weather, Courtesy, and Context

This same precision carries into how Japanese pilots communicate. Before every pilotage, the pilot discusses the weather, carrying the latest wind and tide updates cross-checked with the booklet’s correction tables. The briefing is technical and structured, delivered without unnecessary chatter, patient listening, and quiet confirmation that characterize Japanese bridge culture.

I have worked with pilots elsewhere who handle harsher conditions with great skill. But the key difference is context. In Japan, even exceptional skill sits inside a stronger supporting structure. The system does not depend on individual brilliance, it enables it.

Comparing Systems – How the Rest of the World Works

Around the world, pilotage systems vary greatly. In northern Europe, pilots are highly trained and supported by digital tools, PPUs with ECDIS overlays, and VTS integration, yet the system relies largely on the individual pilot’s judgment rather than a uniform national structure.

In high-tempo ports, planning is often compressed. I have seen final tug positions confirmed only after the tug arrives alongside, and the environment allows little time for structured review.

In many developing regions, documentation exists ashore but not consistently on the bridge, leaving each pilot to work by his own method. When that pilot retires, much of the local wisdom retires with him.

Japan stands apart by capturing that wisdom in print. Annual updates to pilot booklets, tide tables, and procedures transform experience into institutional memory shared with every ship.

Professionalism by System, Not by Personality

The greatest strength of the Japanese model is that it treats professionalism as a system, not a personal trait. The pilot’s authority is clear, but so is his accountability. Every form, signature, and procedural phrase exists to reduce human error and ensure cooperation.

When a Japanese pilot boards, he simply executes a pre-validated plan. The Berth Master does not “coordinate”, he follows a written sequence. The tug master does not guess, he acts on a shared diagram. Ambiguity simply does not enter the operation.

In many ways, Japanese pilotage resembles aviation, pre-flight checklists, signed clearances, standard phraseology, and mutual respect. It is professionalism made visible.

What the Rest of Us Can Learn

There are lessons here for every port, every pilot, and every shipmaster:

- Information Sharing – Give all parties the same data early; most errors disappear before they begin.

- Documentation as Culture – Good paperwork is discipline, not bureaucracy.

- Predictability Equals Safety – Routine planning removes last-minute risk.

- Courtesy as a Safety Tool – Respectful communication improves clarity under pressure.

- Continuous Standardization – Updating pilot manuals and tide tables turns local experience into national consistency.

Reflections from the Bridge

Standing on the bridge wing of a deep-draft VLCC as the tugs take their lines, I’ve often compared these moments with similar operations elsewhere. In Japan, the pilot rarely raises his voice, the tug master seldom calls twice, and the berth master’s gestures are minimal but clear. The tugs approach, stop, and make fast exactly at the pre-assigned points, no calls, no corrections, no surprises.

Everyone shares the same picture in their head.

Elsewhere, even good ports can slip into small bursts of chaos, a rushed call, a tug on the wrong quarter, or a line let go a moment too early. The ship still berths safely, but the difference shows in stress, timing, and workload.

Professionalism, I have learned, is not the absence of error, it is the structure that prevents error from multiplying. Japan demonstrates that every day.

Pilot errors do occur in Japan, as they do everywhere, but when the bridge team spots a deviation, the correction is offered and accepted calmly and professionally. No ego, no debate, just a quiet return to the plan.

Closing Thoughts – The Culture of Predictable Excellence

When a pilot in Tokyo Bay or Nagoya approaches your gangway, it is clear that this is not an individual effort but a national habit. Every checklist and planning document reflects years of refinement. The process is designed to work flawlessly and not to impress.

In Japan, professionalism has been engineered into the maritime system itself. It does not depend on who is on watch or which pilot boards your ship, it simply happens the same way, every time.

The lesson is not to imitate Japanese culture, but to recognise that true professionalism is never spontaneous. It is planned, rehearsed, documented, and continuously improved.

As Masters, we often say a ship moves best when everyone is thinking one step ahead of her movement.

In Japan, the entire port seems to think that way.

References & Notes

• Japan Coast Guard Hydrographic and Oceanographic Department – Tide & Current Tables (Tokyo Wan, Ise–Mikawa Wan)

• Tokyo Bay Licensed Pilots’ Association – Pilotage Instructions & Passage Planning Guidelines

• Nagoya Bay Pilots – Berthing Operation Information Card

• International Maritime Pilots’ Association (IMPA) – Best Practices in Pilotage

• Author’s operational experience across North America, South America, Asia, Middle East, and Africa (2006–2025)

Leave a comment