In the past five years, the shipping industry has seen a disturbing rise in deaths and disappearances among young seafarers, many recorded as suicides or “unexplained” at-sea cases.

Insurers now list suicide as a significant share of crew fatalities, and NGOs warn the true toll may be higher because of inconsistent reporting.

One case, still unfolding, shows why this matters.

On September 20, 2025, a 22-year-old deck cadet on the oil tanker Front Princess was reported missing off the Sri Lankan coast while the ship was en route from Iraq to China. The management company says he is suspected to have been lost overboard. A 96-hour search by the crew and Sri Lankan authorities found no trace. His family has sought official intervention and a thorough probe. As of now, no recovery or cause has been confirmed and the conflicting narratives underline a hard fact. Headlines rarely tell the whole story.

Just four days later, another tragedy struck closer to Europe. On 24 September, a 20-year-old engine cadet aboard the Greek ferry Blue Star Chios was fatally crushed by a watertight door while on duty. He had joined the vessel barely a week earlier, holding valid STCW certification and having completed safety familiarization. Yet the system still failed him.

Greek authorities later arrested the ship’s captain and chief engineer on charges of manslaughter by negligence, while maritime unions launched a 24-hour strike demanding stricter safety oversight.

These are not isolated events, they form a pattern – young, qualified seafarers dying in preventable circumstances under systems that claim to protect them.

The blurred lines that hide the truth

Between “suicide,” “accident,” and “natural causes,” the truth often disappears.

There is no single, transparent global database for deaths or disappearances of seafarers. Instead, information is scattered across flag-state casualty reports, P&I club case records, company statements, and local investigations. In many cases, data is either unpublished or anonymized under privacy or jurisdictional constraints, leaving families and unions to reconstruct events from partial evidence and scattered media reports.

This lack of a central record is not a minor administrative gap. It shapes the entire narrative. Without consistent classification or public reporting, it becomes difficult to distinguish genuine suicides from possible occupational deaths or foul play. The result is a pattern of uncertainty that obscures accountability and weakens prevention.

The question that changed how I see command

I joined the profession for what most young men of my generation saw in it, the promise of the world. To travel, to see places, and yes, to earn well. The images we grew up with were pure glamour with a captain on the bridge in mirrored sunglasses, two elegant women beside him, the open sea behind. It looked confident, adventurous, and free.

That dream was powerful enough to pull many of us in.

But reality came fast. The sea is not a postcard. It tests your patience, endurance, and dignity. And for many cadets today, the distance between what they expect and what they find onboard can be brutal. When mentorship fails, that disillusionment becomes dangerous.

Years later, I realised this crisis isn’t abstract. It begins with how we train, how we lead, and how we listen at sea.

During my Master’s oral exam in 2010, Captain Khatri (Nautical Surveyor-cum-DDG (Tech))questioned me relentlessly on pilotage, General Average, the Himalaya Clause, every subject which I remember that defines command. After hours of law and seamanship, he paused, looked up, and asked a question I wasn’t prepared for –

“You are the captain of a ship, and a new cadet joins onboard. How will you handle him? And if he comes to you with a complaint, how will you handle that?”

That single question broke through everything I thought command meant.

I stopped thinking like a master candidate and started remembering what it felt like to be a cadet.

Back then, dignity was the first thing you lost. You weren’t called by your name. You were shouted at for mistakes you hadn’t yet learned to avoid. Tasks meant to train you often became punishment. Some of us adapted, others quietly fell apart.

That difference between the academy’s promise and the reality onboard is where the system begins to fail. It’s not a gap in seamanship. It’s a gap in leadership. And that gap has cost lives.

Not just “mental health”: what actually breaks cadets

When headlines reduce these deaths to “mental health,” they miss the machinery behind despair. For many cadets, the pathway is social and structural:

- Harassment disguised as training. Seniors equate respect with weakness & humiliation becomes a teaching method.

- Isolation and silence. Long contracts and poor communication leave cadets trapped without independent support.

- Unsafe, unsupervised work. Cadets are often assigned heavy or hazardous tasks alone, jobs that should be carried out by trained crew under proper supervision.

- Fear of speaking up. Many remain silent to avoid being labelled weak or unfit, fearing blacklisting if they complain.

These aren’t hypotheticals. P&I clubs and accident investigators have reviewed such cases repeatedly, and the pattern is consistent – context kills, not just circumstance.

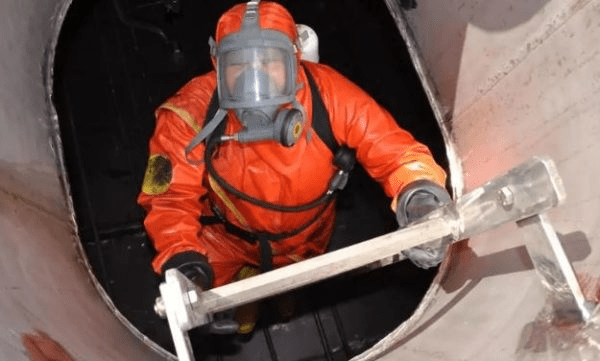

I remember my own cadetship on a product tanker. We were four cadets onboard with a full crew. For tank entries and cleaning, when ratings demanded extra overtime, the chief officer sent us instead. We entered the cargo tanks with portable pneumatic pumps to strip residual oil and water from the bilge-well, working in what were always enclosed spaces. This was the early 2000s, when the ISM system was still finding its feet, and commercial pressure on deck officers often outweighed developing safety culture.

Sometimes, gas readings were not within safe limits, yet the job went ahead.

The air inside carried vapours of paraxylene and naphtha from previous cargoes, and even with ventilation, the atmosphere was harsh and suffocating. I remember cadets coming out gasping for breath, sometimes vomiting on deck after a few minutes inside. Looking back, one wrong breath or one faint step could have been fatal. It wasn’t courage that kept us going, it was a culture that normalised risk and called it training.

I still remember one incident from my cadetship that has stayed with me.

While crossing the Dover Strait in winters, a cadet went missing during the night. Next day, the alarm was raised, and the Dover Coast Guard was alerted. For nearly three days, the vessel searched in freezing conditions amid heavy traffic. Everyone feared the worst, and the family was informed through the company.

But when the ship reached the next port, the unthinkable happened, the cadet reappeared. He had been hiding for days inside the steering flat, surviving on biscuits and water, helped quietly by a few ratings who took pity on him. He said he could no longer bear the treatment he was receiving from the chief officer.

That episode taught me something lasting, despair at sea does not always look like a suicide. Sometimes, it’s a young person pushed beyond endurance, disappearing into the machinery of the ship because there is nowhere else to go.

Balance: accountability cuts both ways

Fairness matters. Not every complaint at sea is genuine, and not every cadet is blameless. I have seen cases where cadets misuse welfare channels by refusing legitimate training assignments, exaggerating grievances, or invoking mental health or harassment claims as a shield against accountability. A ship cannot function when authority is constantly second-guessed, or when discipline becomes negotiable.

I also see another pattern. Many senior officers, including chief officers who now act as training officers, still measure today’s cadets against their own pasts. The logic is simple: “We went through worse and survived, so they should too.” It’s a powerful but misplaced belief. What it overlooks is that the world, technology, and expectations have changed. Training cannot be an act of revenge for one’s own suffering. It must be an act of teaching, shaped by empathy and responsibility.

I still remember cadetship during the 2000s on product tankers. A full cargo discharge could run 24 to 30 hours straight, followed immediately by tank cleaning and subsequent operations. It wasn’t unusual to go three or four days without real rest, dozing on ropes or on deck between jobs. It was one of the hardest periods of my life, but it taught endurance and accountability that no classroom could replicate.

At the same time, I now see the opposite extreme taking root. Some companies, fearing negative publicity or regulatory scrutiny, have made cadet handling so cautious that it borders on theatrical. Cadets are told to “stand by” on the bridge wings instead of participating in mooring. They observe cargo operations from a distance but never touch a valve or line. They are given separate work hours, long rest periods, and even Sunday celebrations onboard while critical operations on the vessel is going on.

The training budgets for cadets today are generous ,perhaps rightly so, but they’ve also created a strange divide. Cadets arrive with laptops, structured learning guidance ,scheduled shore leave, sometimes with dedicated launches arranged exclusively for them. I don’t mind the comforts, every generation deserves better than the last. What troubles me is the timing. Even when critical operations are underway like cargo discharge, tank cleaning, audits, inspections or change-over, a shore-leave board arranged by the training department often takes precedence.

Instead of being on deck, observing and learning, cadets are ferried ashore in the middle of the very experiences that once defined our foundation. The crew may not say much, but they notice. The message this sends is subtle yet corrosive, that training is about entitlement, not engagement. And one day, these same cadets will return as officers, expected to lead teams in operations they were never truly part of.

It may look progressive or protective, but it is quietly counterproductive. A cadet who is never exposed to the routine, the sweat, and the responsibility of shipboard work does not become resilient, he becomes ornamental. You can’t build a competent officer out of a sheltered observer. In trying to avoid risk, we are producing soft professionals who lack confidence, situational awareness, and instinct, the very qualities that keep ships safe.

I see the results of that change every day. Young second mates, bright, qualified, and barely a few ships old come to me and say, “Captain, this is too hard. How can we join shore?” They’re not weak, they’re unprepared. Their resilience wasn’t built because their training shielded them from hardship. These are early warning signs when young officers already feel broken, it tells us how fragile the foundation has become.

When resilience weakens, despair finds room to grow. What we call “mental health” at sea often begins with lost mentorship, not lost sanity. That’s why prevention cannot stop at slogans, it must start with how we train, how we lead, and how we listen.

When “natural” isn’t natural

Not every tragedy is caused by harassment. Some cadets die doing work they were untrained for, others collapse from dehydration, exhaustion, or exposure.

Labeling such cases “natural causes” can be an evasion. Management decisions, poor supervision, unrealistic workloads, lack of rest can often turn manageable risks into deaths.

Calling it “natural” cannot become the industry’s shortcut to avoid responsibility.

What would actually save lives

It’s time to move beyond platitudes. These are steps every company and academy could adopt now:

- Mentorship with accountability.

Each cadet should have a named mentor whose performance is audited by captain, chief-engineer or shore management, with clear training objectives and sign-offs. - Zero tolerance for bullying, with due process.

Treat harassment like any safety violation. Investigate fast, protect the cadet temporarily, but without presuming guilt. - Anonymous, independent reporting.

Digital, third-party channels (run by unions or neutral bodies) with whistleblower protection and time-bound responses. - Shore-side welfare check-ins.

Scheduled one-to-one calls with cadets, not filtered by the Master to surface problems early. - Code of conduct for cadets.

Clear expectations and transparent consequences for misconduct, ensuring protections aren’t one-sided. - Mandatory, transparent investigations.

Every cadet death or serious injury must trigger a public summary (redacted for privacy) to prevent contradictory narratives.

Transparency is part of prevention

Every cadet death is layered with human, institutional, and moral, some are caused by harassment, others by fatigue or neglect, and too many remain uncertain because the system prefers silence.

That ambiguity is not neutral, it protects wrongdoers and punishes families.

Captain Khatri’s question wasn’t about seamanship, it was about leadership.

How we answer it now will decide whether we save the next generation of seafarers or keep losing them, one report at a time, to the silence between official log entries and incident investigation reports.

References

- ISWAN (International Seafarers’ Welfare and Assistance Network). Seafarers’ Mental Health and Wellbeing Report. 2022.

- ITF Seafarers’ Trust. Suicide and Mental Health at Sea: The Hidden Crisis. 2023.

- UK P&I Club. Crew Health Programme Report. 2023.

- The Times of India. “Cadet Missing from Oil Tanker off Sri Lanka Coast.” 24 September 2025.

- International Transport Workers’ Federation (ITF). Seafarer Deaths and Disappearances Study. 2020.

- European Maritime Safety Agency (EMSA). Annual Overview of Marine Casualties and Incidents. 2024.

- ISWAN & ICS (International Chamber of Shipping). Guidelines on Mentoring for Seafarers. 2021.

- Greek Ministry of Shipping, PEMEN Union, and maritime press reports on the Blue Star Chios (IMO 9215555), incident dated 24 September 2025.

Leave a comment