The Ghost of Dali: A Wake-Up Call

The maritime fraternity has never fully exorcised the ghost of MV Dali. In March 2024, the containership, while transiting the Patapsco River near Baltimore, suffered a cascading electrical blackout that left its propulsion and steering systems inoperable. Without control, the vessel struck the Francis Scott Key Bridge, collapsing several spans and tragically killing six maintenance workers. The National Transportation Safety Board’s investigation confirmed multiple electrical power losses and continues to examine the ship’s electrical distribution and the sequence of breaker trips that led to the loss of propulsion and steering (NTSB, 2024).

For the wider public, it was a shocking headline. A runaway ship, a destroyed bridge, and lives lost. But for seafarers and shipmasters, the Dali incident was more than a single failure, it was a symptom of chronic systemic weaknesses like deferred maintenance, inadequate spare-parts resilience, cascading electrical failures, and shore management disconnected from operational realities.

Dali’s ghost still haunts the industry. It is a reminder that a chain of technical and managerial compromises can suddenly become catastrophic. And it sets the stage for a newer, more instructive case of the MSC Michigan VII Chief Engineer, Fernando San Diego San Juan whose story illustrates how systemic pressures can leave a seasoned engineer personally liable, while the wider machinery of the shipping industry escapes scrutiny.

A Short Story of What Happened: MSC Michigan VII

On June 5, 2024, while departing Charleston Harbor, the vessel’s main engine governor linkage detached. The ship became momentarily unresponsive to bridge orders and surged ahead at 15–17 knots, more than double the legal harbor limit. The pilots informed the authorities immediately who closed the Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge and cleared nearby beaches as a precaution. The U.S. Coast Guard detained the vessel for inspection before later lifting the detention order.

At the center of the public story was Fernando San Juan, 61 years old, the Chief Engineer aboard MSC Michigan VII. Federal prosecutors alleged that he failed to report hazardous conditions and obstructed investigators by providing misleading statements and encouraging crew to do the same. San Juan ultimately entered a plea agreement, admitting to failing to report a hazardous condition and to obstructing an agency proceeding.

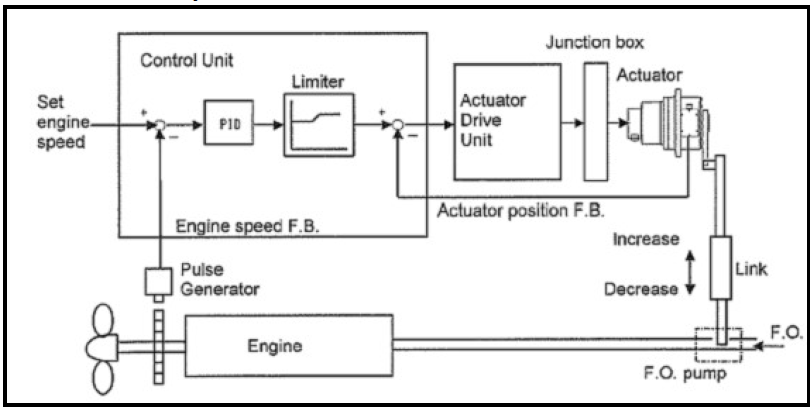

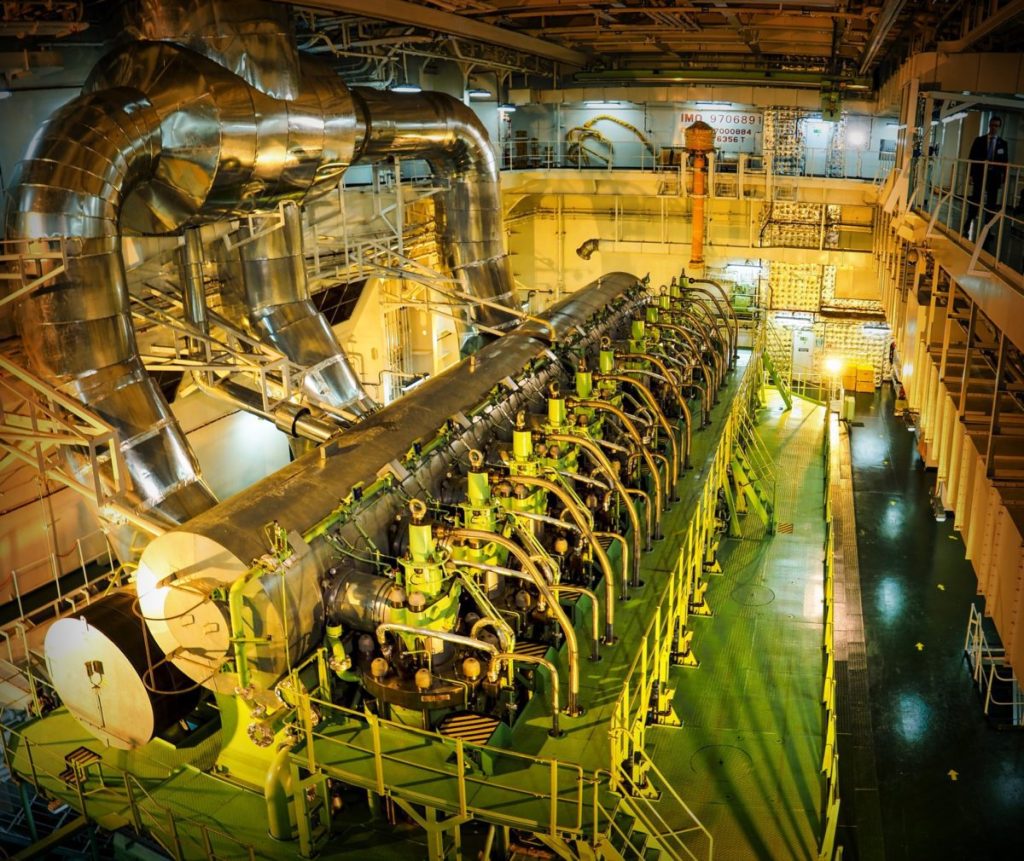

Court filings describe a ship whose engineering team had been coping for months with repeated equipment issues, often relying on manual adjustments of the governor linkage to meet RPM commands during maneuvers. The need for such a workaround was linked to persistent fuel-injection problems caused by the use of low-sulfur distillate fuel (LSMGO) mandated in U.S. Emission Control Areas (ECA). These fuels, while environmentally required, have lower viscosity and lubricity, which can accelerate wear in high-pressure fuel pumps and injectors, leading to internal leakage and inconsistent fuel delivery. When the governor’s automatic control could not reliably achieve ordered RPMs, engineers resorted to manually biasing the governor linkage to force more fuel into the cylinders, a temporary workaround that became routine due to persistent ECA fuel-induced wear.

Over time, repeated handling and vibration weakened the fittings until the rod ultimately detached, leaving propulsion uncontrollable.

Those are the immediate facts and technical realities combined. What is less obvious and where the hard lessons lie is how organizational pressures, deferred maintenance, and systemic operational compromises transformed a temporary, emergency workaround into a potentially catastrophic failure.

When “Human Error” Becomes System Collapse

Modern maritime investigations often default to a shorthand explanation – human error. It’s tidy, easily digestible for headlines, and satisfies public expectations for accountability. Yet human error rarely exists in isolation. It is almost always the final link in a chain of systemic factors, including:

- Fatigue and compressed work cycles, leaving crew less alert during critical maneuvers.

- Reduced spare-part inventories, forcing operators to improvise repairs.

- Deferred maintenance and prolonged operational compromises, which gradually weaken machinery.

- Compressed handovers, limiting the incoming officer’s understanding of ongoing issues.

- Managerial messages, both explicit and implicit, prioritizing schedule and cargo delivery over safe downtime.

In the MSC Michigan VII case, court filings highlighted an abbreviated handover window and chronic mechanical deficiencies. The temporary manual workaround for the governor linkage exemplifies how systemic pressures transform minor technical issues into high-risk situations.

These improvisations shift risk from visible mechanical defects to opaque crew practices, where a single failure can escalate into a public safety event. Shipping insurance adds another layer of complexity. Protection & Indemnity (P&I) insurance often covers operational mistakes by the crew, usually categorized as crew negligence.

Systemic shortcomings such as deferred maintenance, inadequate spares, or flawed shore directives, however, may not be fully insured. This creates a scenario where the crew bears legal and financial exposure for failures that are ultimately rooted in organizational weaknesses.

Barring a few standard and reputable companies, this scenario is common across the shipping industry, crews innovate to keep vessels operational, managers approve departures for commercial reasons, insurers protect some operational risks but not systemic failures, and auditors or regulators often remain unaware until an incident occurs. When failure strikes, the person on watch becomes the face of accountability, the name on a charge sheet, while the systemic pressures that created the vulnerability remain largely invisible.

Technical Management: Shore Control, Superintendents, and the Competence Gap

Modern shipping relies increasingly on centralized shore-side technical management, creating a structural distance between decision-makers and the engineers managing machinery onboard. In many companies, the heads of fleet technical departments are not always former Chief Engineers. The HODs may appoint junior engineers, dual-certified officers, or even deck officers to technical management roles, individuals who are often less likely to challenge directives. While intended to streamline operations, this structure can weaken technical oversight and operational judgment, leaving crews to manage systemic and mechanical challenges largely on their own.

In this context, it has also been widely observed that senior Chief Engineers sailing on board are often unconvinced by directives issued by comparatively junior superintendents ashore, and their response tends to be more resentful than compliant. This disconnect underscores a growing cultural and experiential gap between those who make technical decisions onshore and those who must execute them at sea.

Evolution of Superintendent Role

Superintendents, some of whom have never borne the full responsibilities of a Chief Engineer, or have served only a single tenure in that capacity now often coordinate with other sailing Chief Engineers or relay issues to manufacturers or shore-based specialists rather than directly troubleshooting machinery. While this approach can improve standardization and information flow, it reduces hands-on engagement and shifts operational risk onto the vessel. Temporary fixes, deferred maintenance, and procedural shortcuts become normalized, especially under commercial pressure or when spare-part inventories are limited.

The MSC Michigan VII incident illustrates the consequences, chronic mechanical issues, constrained spares, and reliance on manual workarounds combined with dispersed shore-side directives left the Chief Engineer, despite decades of experience, as the primary face of accountability, even though the root causes were systemic.

Cost Cutting, Spares, and Deferred Maintenance

Spare parts are costly, and logistics for critical engine components can be slow and complicated. Under commercial pressure, ships often operate with reduced spare inventories, deferred maintenance, and postponed overhauls.

In MSC Michigan VII, persistent leaks and faults in the fuel injection pumps, fuel lines, and auxiliary fuel pumps affected the delivery of fuel to the main engine cylinders. To maintain engine performance and achieve commanded RPMs during maneuvers, the crew was forced to manually adjust the governor linkage as a workaround. Limited spare availability forced the crew to rely on temporary workarounds. Every decision to postpone maintenance or reduce spare inventories magnified latent risk, turning routine cost-cutting into a safety hazard with legal consequences for onboard personnel.

Defect Reporting and Near-Miss Management

Defect reports and near-miss reports are intended to be the cornerstone of organizational learning and operations in shipping. Properly handled, they allow crews and management to identify latent hazards, trigger risk assessments, allocate or procure critical spare parts, and notify classification societies, flag administrations, and port authorities when necessary. This structured approach ensures preventive action before minor technical issues escalate into major incidents.

In reality, however, the reporting system is often subverted by commercial and bureaucratic pressures. Many companies set KPIs for near-miss reporting, requiring a minimum number of events per month. To meet these targets, vessels may submit minor or irrelevant reports, while truly critical hazards go unreported to avoid investigations, follow-up questioning, or operational delays. Similarly, defect reports for critical equipment are often logged only after the defect is rectified, to avoid triggering regulatory scrutiny, short-term certification, additional inspections, or unplanned costs. Outcomes that operators are incentivized to minimize.

This flawed approach undermines the purpose of both systems. Important lessons are lost, latent risks persist, and hazards remain hidden until they manifest in incidents, leaving crews and management exposed. In the case of MSC Michigan VII, issues with fuel supply system components led to manual governor adjustments, a workaround that could have been prevented with timely and transparent defect reporting.

Ultimately, near-miss and defect reporting systems are only effective if reporting is meaningful, timely, and followed by concrete action. Without this, safety systems exist largely on paper, and systemic risks continue to accumulate, waiting for the next preventable accident.

Handover Failure: The 5-Hour Gap That Mattered

Handover is deceptively simple but crucial. IMO guidance stresses face-to-face exchange and adequate review of logs, defects, and ongoing repairs. In MSC Michigan VII, the incoming Chief Engineer had only a five-hour handover, far shorter than recommended. As a result, latent defects and established workarounds became his immediate responsibility, setting the stage for cascading failure.

The problem is compounded by crew travel and fatigue. Senior officers often arrive at their vessels after 24–36 hours of continuous travel involving paperwork, medical checks, flights, layovers, and multiple time zone changes. In many cases, they step on board immediately upon arrival and are expected to take charge of safety-critical systems without meaningful rest. This creates a dangerous situation where handover is rushed, fatigue & jet lag is at its peak, and critical details are missed.

A practical solution lies in reframing how rest is managed. Travel time should be recognized as transit duty, not rest. To make this meaningful, there should be a mandatory hotel stay of at least 8–12 hours before joining the ship, particularly for senior officers whose decisions directly affect safety. This would ensure that crews take over with clear judgment and adequate recovery, rather than under the haze of travel fatigue and jet lag.

However, for such practices to take root, regulatory frameworks like the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC) must evolve to explicitly recognize transit fatigue and time-zone disruption as occupational risk factors. Managers and crewing offices largely operate within regulatory dictates; unless these standards formally define travel-related fatigue as duty time, commercial and scheduling pressures will continue to override rest and safety.

Legal Exposure: Why the Seafarer Becomes the Face of Accountability

The MSC Michigan case once again demonstrated a familiar pattern in maritime law enforcement. When something goes wrong, it is usually the seafarer, not the company, not the shore office, not the procurement system who ends up in the courtroom. Prosecutors focused on Fernando San Juan’s failure to report hazardous conditions and his misleading statements, because he was physically present and held formal authority.

This focus on the individual makes legal sense, but it raises an uncomfortable imbalance. Onboard personnel can face prison time, fines, loss of certification, and permanent reputational harm in a tight-knit industry. Meanwhile, the systemic factors that shaped their decisions like commercial schedules, cost-cutting on spares, managerial pressure, or inadequate handovers rarely face the same level of scrutiny or accountability.

Until legal frameworks distribute responsibility more evenly between ship and shore, the Chief Engineer or Master will remain the easiest target of accountability, even when they are simply the last visible link in a much longer chain of decisions and pressures,

Safety Culture vs. Commercial Reality

Every vessel displays the company’s Safety and Environmental Policy, which may have limited impact on day-to-day operations. Crews sail with deferred defects, improvised fixes, and commercial pressure that overrides the slogans. A genuine safety culture needs investment in spares, accountability ashore, and protection for those who report concerns otherwise, it remains a poster on the wall, not a practice on board.

Toward Systemic Accountability

For the maritime sector to achieve lasting safety improvements, reforms must go beyond compliance documents and marketing slogans:

- Hardened handover and watchkeeping standards

- Minimum-duration handovers with face-to-face briefings and auditable documentation to ensure incoming officers fully understand ongoing defects, workarounds, and operational nuances.

- Spare-part resilience and planned maintenance

- Verified inventories of critical engine and propulsion components, with penalties for chronic deferrals. Ensure procurement timelines account for obsolete or hard-to-source parts to prevent operational improvisation.

- Shared shore-vessel accountability

- Legal and operational frameworks that hold shore managers responsible for decisions that shift risk onto the crew. Onboard personnel should not be the sole bearers of consequences when systemic pressures compromise safety.

- Robust near-miss reporting and a just culture

- Anonymous, third-party reporting systems protecting whistleblowers from retaliation. Encourage meaningful reporting rather than “KPI-filling” superficial entries.

- Transparent investigations that publish lessons

- Redacted, publicly available root-cause analyses so the industry can learn from incidents without placing undue blame solely on the seafarer.

Change the Question, Not Just the Defendant

Fernando San Juan’s case is both personal and structural. A 61-year-old engineer with decades of experience now faces severe consequences. But the real lesson lies in systemic accountability:

- What cost pressures, managerial decisions, and regulatory gaps allowed manual linkages to become standard practice?

- What organizational norms made a technically skilled officer the only person legally accountable?

Until the industry answers these questions, every Chief Engineer knows the script, when failure occurs, the blame will be theirs, and the system will have learned only how to hide the same vulnerabilities, rather than prevent them.

Sources

- US Coast Guard, “MSC Michigan VII released from detention in Charleston.” USCG News

- Maritime Executive, “Chief Engineer Pleads Guilty in 2024 MSC Runaway Incident.”

- gCaptain, “Runaway Ship: Chief Engineer Pleads Guilty After Charleston Bridge Scare.”

- IMO resources on Safety Management and the ISM Code

- OCIMF, “Engineering Watch, Duty Periods, and Inspection Routines”

- Legal and academic critiques of flags of convenience and regulatory implications

- Industry discussions on spares, deferred maintenance, and operational impacts of cost-cutting

This article is an opinion piece by the author and does not reflect the official position of any company, organization, or regulatory body. All factual references are drawn from publicly available sources and news reports.

Leave a comment